Posted by Joel Galenson and Matthew Maurer, Android Team

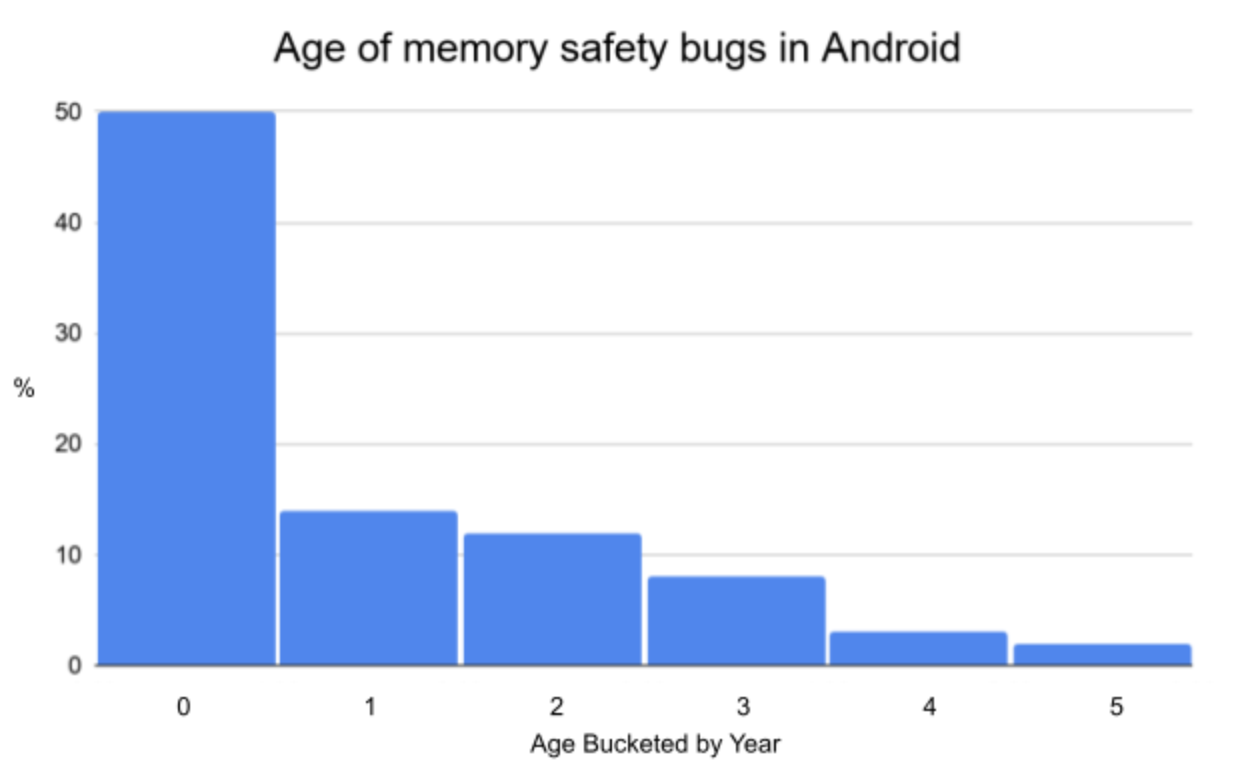

One of the main challenges of evaluating Rust for use within the Android platform was ensuring we could provide sufficient interoperability with our existing codebase. If Rust is to meet its goals of improving security, stability, and quality Android-wide, we need to be able to use Rust anywhere in the codebase that native code is required. To accomplish this, we need to provide the majority of functionality platform developers use. As we discussed previously, we have too much C++ to consider ignoring it, rewriting all of it is infeasible, and rewriting older code would likely be counterproductive as the bugs in that code have largely been fixed. This means interoperability is the most practical way forward.

Before introducing Rust into the Android Open Source Project (AOSP), we needed to demonstrate that Rust interoperability with C and C++ is sufficient for practical, convenient, and safe use within Android. Adding a new language has costs; we needed to demonstrate that Rust would be able to scale across the codebase and meet its potential in order to justify those costs. This post will cover the analysis we did more than a year ago while we evaluated Rust for use in Android. We also present a follow-up analysis with some insights into how the original analysis has held up as Android projects have adopted Rust.

Language interoperability in Android

Existing language interoperability in Android focuses on well defined foreign-function interface (FFI) boundaries, which is where code written in one programming language calls into code written in a different language. Rust support will likewise focus on the FFI boundary as this is consistent with how AOSP projects are developed, how code is shared, and how dependencies are managed. For Rust interoperability with C, the C application binary interface (ABI) is already sufficient.

Interoperability with C++ is more challenging and is the focus of this post. While both Rust and C++ support using the C ABI, it is not sufficient for idiomatic usage of either language. Simply enumerating the features of each language results in an unsurprising conclusion: many concepts are not easily translatable, nor do we necessarily want them to be. After all, we’re introducing Rust because many features and characteristics of C++ make it difficult to write safe and correct code. Therefore, our goal is not to consider all language features, but rather to analyze how Android uses C++ and ensure that interop is convenient for the vast majority of our use cases.

We analyzed code and interfaces in the Android platform specifically, not codebases in general. While this means our specific conclusions may not be accurate for other codebases, we hope the methodology can help others to make a more informed decision about introducing Rust into their large codebase. Our colleagues on the Chrome browser team have done a similar analysis, which you can find here.

This analysis was not originally intended to be published outside of Google: our goal was to make a data-driven decision on whether or not Rust was a good choice for systems development in Android. While the analysis is intended to be accurate and actionable, it was never intended to be comprehensive, and we’ve pointed out a couple of areas where it could be more complete. However, we also note that initial investigations into these areas showed that they would not significantly impact the results, which is why we decided to not invest the additional effort.

Methodology

Exported functions from Rust and C++ libraries are where we consider interop to be essential. Our goals are simple:

- Rust must be able to call functions from C++ libraries and vice versa.

- FFI should require a minimum of boilerplate.

- FFI should not require deep expertise.

While making Rust functions callable from C++ is a goal, this analysis focuses on making C++ functions available to Rust so that new Rust code can be added while taking advantage of existing implementations in C++. To that end, we look at exported C++ functions and consider existing and planned compatibility with Rust via the C ABI and compatibility libraries. Types are extracted by running objdump on shared libraries to find external C++ functions they use1 and running c++filt to parse the C++ types. This gives functions and their arguments. It does not consider return values, but a preliminary analysis2 of those revealed that they would not significantly affect the results.

We then classify each of these types into one of the following buckets:

Supported by bindgen

These are generally simple types involving primitives (including pointers and references to them). For these types, Rust’s existing FFI will handle them correctly, and Android’s build system will auto-generate the bindings.

Supported by cxx compat crate

These are handled by the cxx crate. This currently includes std::string, std::vector, and C++ methods (including pointers/references to these types). Users simply have to define the types and functions they want to share across languages and cxx will generate the code to do that safely.

Native support

These types are not directly supported, but the interfaces that use them have been manually reworked to add Rust support. Specifically, this includes types used by AIDL and protobufs.

We have also implemented a native interface for StatsD as the existing C++ interface relies on method overloading, which is not well supported by bindgen and cxx3. Usage of this system does not show up in the analysis because the C++ API does not use any unique types.

Potential addition to cxx

This is currently common data structures such as std::optional and std::chrono::duration and custom string and vector implementations.

These can either be supported natively by a future contribution to cxx, or by using its ExternType facilities. We have only included types in this category that we believe are relatively straightforward to implement and have a reasonable chance of being accepted into the cxx project.

We don’t need/intend to support

Some types are exposed in today’s C++ APIs that are either an implicit part of the API, not an API we expect to want to use from Rust, or are language specific. Examples of types we do not intend to support include:

- Mutexes – we expect that locking will take place in one language or the other, rather than needing to pass mutexes between languages, as per our coarse-grained philosophy.

native_handle – this is a JNI interface type, so it is inappropriate for use in Rust/C++ communication. std::locale& – Android uses a separate locale system from C++ locales. This type primarily appears in output due to e.g., cout usage, which would be inappropriate to use in Rust.

Overall, this category represents types that we do not believe a Rust developer should be using.

HIDL

Android is in the process of deprecating HIDL and migrating to AIDL for HALs for new services.We’re also migrating some existing implementations to stable AIDL. Our current plan is to not support HIDL, preferring to migrate to stable AIDL instead. These types thus currently fall into the “We don’t need/intend to support” bucket above, but we break them out to be more specific. If there is sufficient demand for HIDL support, we may revisit this decision later.

Other

This contains all types that do not fit into any of the above buckets. It is currently mostly std::string being passed by value, which is not supported by cxx.

Top C++ libraries

One of the primary reasons for supporting interop is to allow reuse of existing code. With this in mind, we determined the most commonly used C++ libraries in Android: liblog, libbase, libutils, libcutils, libhidlbase, libbinder, libhardware, libz, libcrypto, and libui. We then analyzed all of the external C++ functions used by these libraries and their arguments to determine how well they would interoperate with Rust.

Overall, 81% of types are in the first three categories (which we currently fully support) and 87% are in the first four categories (which includes those we believe we can easily support). Almost all of the remaining types are those we believe we do not need to support.

Mainline modules

In addition to analyzing popular C++ libraries, we also examined Mainline modules. Supporting this context is critical as Android is migrating some of its core functionality to Mainline, including much of the native code we hope to augment with Rust. Additionally, their modularity presents an opportunity for interop support.

We analyzed 64 binaries and libraries in 21 modules. For each analyzed library we examined their used C++ functions and analyzed the types of their arguments to determine how well they would interoperate with Rust in the same way we did above for the top 10 libraries.

Here 88% of types are in the first three categories and 90% in the first four, with almost all of the remaining being types we do not need to handle.

Analysis of Rust/C++ Interop in AOSP

With almost a year of Rust development in AOSP behind us, and more than a hundred thousand lines of code written in Rust, we can now examine how our original analysis has held up based on how C/C++ code is currently called from Rust in AOSP.4

The results largely match what we expected from our analysis with bindgen handling the majority of interop needs. Extensive use of AIDL by the new Keystore2 service results in the primary difference between our original analysis and actual Rust usage in the “Native Support” category.

A few current examples of interop are:

- Cxx in Bluetooth – While Rust is intended to be the primary language for Bluetooth, migrating from the existing C/C++ implementation will happen in stages. Using cxx allows the Bluetooth team to more easily serve legacy protocols like HIDL until they are phased out by using the existing C++ support to incrementally migrate their service.

- AIDL in keystore – Keystore implements AIDL services and interacts with apps and other services over AIDL. Providing this functionality would be difficult to support with tools like cxx or bindgen, but the native AIDL support is simple and ergonomic to use.

- Manually-written wrappers in profcollectd – While our goal is to provide seamless interop for most use cases, we also want to demonstrate that, even when auto-generated interop solutions are not an option, manually creating them can be simple and straightforward. Profcollectd is a small daemon that only exists on non-production engineering builds. Instead of using cxx it uses some small manually-written C wrappers around C++ libraries that it then passes to bindgen.

Conclusion

Bindgen and cxx provide the vast majority of Rust/C++ interoperability needed by Android. For some of the exceptions, such as AIDL, the native version provides convenient interop between Rust and other languages. Manually written wrappers can be used to handle the few remaining types and functions not supported by other options as well as to create ergonomic Rust APIs. Overall, we believe interoperability between Rust and C++ is already largely sufficient for convenient use of Rust within Android.

If you are considering how Rust could integrate into your C++ project, we recommend doing a similar analysis of your codebase. When addressing interop gaps, we recommend that you consider upstreaming support to existing compat libraries like cxx.

Acknowledgements

Our first attempt at quantifying Rust/C++ interop involved analyzing the potential mismatches between the languages. This led to a lot of interesting information, but was difficult to draw actionable conclusions from. Rather than enumerating all the potential places where interop could occur, Stephen Hines suggested that we instead consider how code is currently shared between C/C++ projects as a reasonable proxy for where we’ll also likely want interop for Rust. This provided us with actionable information that was straightforward to prioritize and implement. Looking back, the data from our real-world Rust usage has reinforced that the initial methodology was sound. Thanks Stephen!

Also, thanks to:

- Andrei Homescu and Stephen Crane for contributing AIDL support to AOSP.

- Ivan Lozano for contributing protobuf support to AOSP.

- David Tolnay for publishing cxx and accepting our contributions.

- The many authors and contributors to bindgen.

- Jeff Vander Stoep and Adrian Taylor for contributions to this post.

Posted by Kylie McRoberts, Program Manager and Alec Guertin, Security Engineer

Posted by Kylie McRoberts, Program Manager and Alec Guertin, Security Engineer